Authors: Joy de Vries, Simon Tweddell & Rebecca McCarter.

Abstract

Team-based Learning (TBL) is a new teaching strategy that may take small group learning to a new level of effectiveness. TBL shifts the focus from content delivery by teachers to the application of course content by student teams. Teams work on authentic problems, make collaborative decisions, and develop problem-solving skills required in their future workplace. Prior to redesigning the MPharm programme according to TBL principles, several pilots were set up to research how students responded to this new way of teaching. One pilot focussed on the introduction of TBL as a phenomena and aimed to find out if and how TBL engaged students, how students were held accountable by their teams, and more importantly how that affected their lifeworld. Ashworth’s lifeworld contingencies provided the theoretical framework as it ranges from students’ selfhood, embodiment and social interactions to their ability to carry out tasks they are committed to and regard as essential (Ashworth, 2003).

Problem context

Findings in educational research identified collaboration as an effective social process of knowledge building that requires students working as interdependent teams towards a clear objective resulting in a well-defined final product, consensus, or decision (Wright et al., 2013). The educational practice of our MPharm programme however, still relied heavily on information transmission or content delivery to learners. As practitioners we were challenged to redesign activities requiring collaborative decision making within authentic scenarios. This study helped us to research how TBL would be received by our students and if redesign of the curriculum would ensure learner engagement and accountability.

Theoritical embedding

The student-centred instructional strategy Team-based Learning is firmly grounded within constructivist theory (Hrynchak and Batty, 2012). In constructivist learning theory, the role of teachers shifts from ‘transmitters’ of knowledge to ’facilitators’ of learning (Kaufman, 2003). In TBL students learn how to work collaboratively in teams solving authentic problems related to their future workplace. By creating a setting that facilitates learning how to make collaborative decisions, despite differing opinions, and then justify and defend the team decision, previous research suggests that this method of learning and teaching may help prepare graduates better for the modern workplace (Currey et al., 2015)

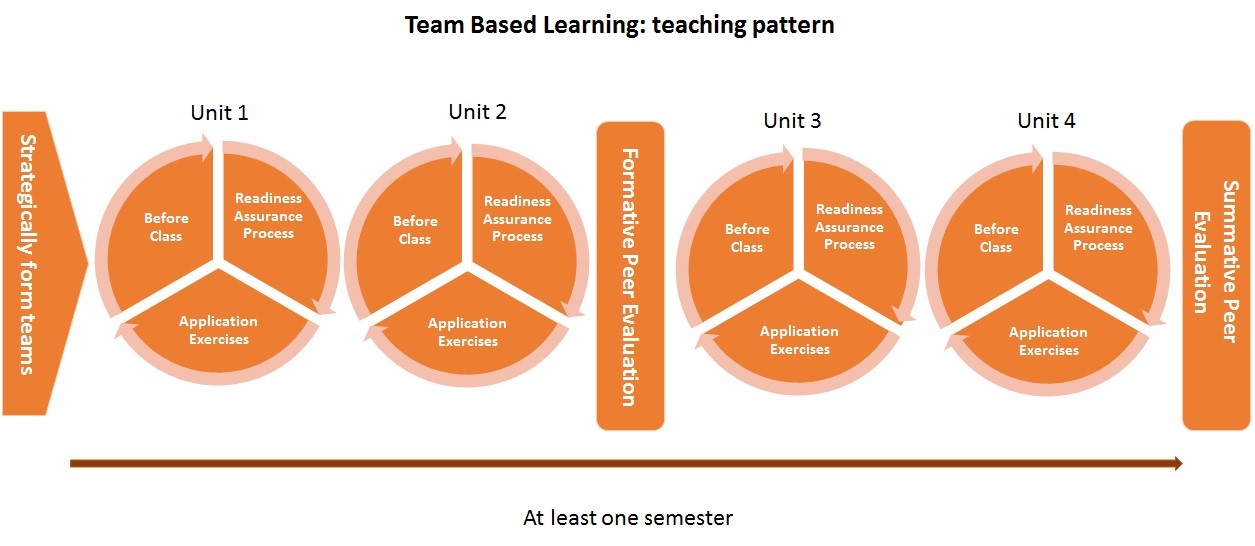

In TBL students work in permanent teams of 5‒7 members.They are given advanced assignments to complete before class. The Readiness Assurance Process consists of an individual assessment followed by a team assessment, to incentivise preparation and attendance and, along with peer evaluation, to develop team accountability. Both assessments are summative. Afterwards instructors give targeted feedback based on these test results. The majority of time in class is spent on application activities designed to develop problem-solving, collaborative decision-making, and promote learning through elaboration, discussion and debate. Figure 1 represents a typical teaching pattern of a TBL module.

Earlier research shows that in TBL students learn how to work collaboratively in teams solving authentic problems and as a result, they report a high level of engagement in TBL modules (Levine et al., 2004; Chung et al., 2009). If and how the introduction to TBL affects student’s lifeworld however, remains unknown.

According to Ashworth the lifeworld is a central concept within phenomenological psychology and seen as an essential structure which is fundamental to all human experience (Ashworth, 2003). The seven contingencies are used to describe the lifeworld as explained in table 1.

Table 1. The lifeworld contingencies as explained by Ashworth.| Life World contingencies | |

|---|---|

| Selfhood | What does the situation mean for the social identity; the person’s sense of agency and the feeling of their own presence and voice? |

| Sociality | How does the situation affect the relation with others? |

| Embodiment | How does the situation relate to feelings about their own bodies, including gender, emotions and disabilities? |

| Temporality | How is their sense of time, duration and biography affected? |

| Spatiality | How is their picture of geography of the places they need to go to and act within affected by the situation? |

| Project | How does the situation relate to their ability to carry out the tasks they are committed to and which they regards as essential to their life? |

| Discourse | What sort of terms, educational, social, commercial, ethical etc. are deployed to describe- and thence to live- the situation? |

Question

How do students’ lived experiences of Team-Based Learning when introduced to it for the first time, affect the contingencies of their lifeworld.

Methods

The methodological orientation is towards phenomenology in which philosophical principles are used to study the way a phenomenon appears to our consciousness. Any experience or event that presents itself to our consciousness can be studied by phenomenology because it does not matter whether the phenomenon is real, imagined, empirically measurable or subjectively felt. If we are aware of it, it is part of our consciousness and therefore part of our world (van Manen, 2014). Phenomena are always someone’s lived experiences, hence data are considered subjective and personal (van Manen, 2014).

The pilot involved final year students taking one module of the undergraduate MPharm programme. Student teams were provided with authentic patient case-based application exercises and asked to make a collaborative decision to justify this to other teams. Facilitators drew out discussion, facilitated debate, and optimised deep approaches to learning.

Data collection

Participants

Following ethical approval, five students in their early twenties (3 male, 2 female) from a cohort of 88 volunteered to take part in an interview or focus group, designed to elicit the lived experiences of students who were introduced to TBL for the first time. In this study a convenience sample was used; the entire cohort was invited to participate and five participants volunteered to take part in the study. The five students were from different teams. Students were given the choice of which data collection method they preferred.

Instruments

Two students elected for individual interview and three for focus group using identical semi-structured questions. Data were transcribed verbatim and subjected to interpretative analysis. Students were given a participants’ number to ensure anonymity and results were only used once for research purposes.

Data analysis

Team members listed their own biases prior to data analysis and researchers first individually coded the data on a line-by-line basis using the life world contingencies as a template. Open codes were discussed and the coding structure was compared against transcripts and existing literature, until a deeper understanding was reached. Ashworth’s lifeworld contingencies provided the theoretical framework for analysis (Ashworth, 2003). Data analysis revealed two main themes: engagement and accountability. Subthemes related to contingencies in students’ lifeworld (see table 2).

Results

Students spoke about all seven life world contingencies when exposed to TBL for the first time. As a team students seemed to be engaged and committed to carry out tasks (project). They felt that contributing to the team effort in an engaging way helped their learning (selfhood). Students believed that they benefited from collaborative discussions and felt teamwork enhanced their collaborative skills (sociality). Students held strong opinions on those who were not engaged and did not contribute (discourse). Students also believed that they benefited from being held accountable indicating a shift in their motivation from not being motivated to prepare for classes, to wanting to be prepared prior to attending class (selfhood, embodiment). Suggestions for improvement were related to application sessions during which they believed time could be managed better (temporality). Students indicated that the reduction of the number of people during those sessions would be an improvement (spatiality, embodiment) and help their learning within the given setting.

Table 2. Students’ quotes organised by Ashworth’s lifeworld contingencies (focus group P1, P2 & P3, interviews P4& P5).| Lifeworld contingencies | Engagement | Accountability |

|---|---|---|

| Selfhood | "The team test when you’ve and every one in your group has pulled their weight in the team discussion this has a lot more impact." (P2) | "Sometimes with lectures you’d just leave it last minute; you can’t do that with this you have to keep the work constant." (P3) |

| Sociality | "It’s good, we have our ups and downs. I mean to be honest in our group four of us have got really similar thinking and one has a different method of thinking but we find our way around it." (P4) | "Sometimes if there’s no driving force and no one to take that first step then sometimes the group just lingers around and stagnates, asking each other ‘ shall we do this, shall we do that’ sometimes you need someone to say let’s choose this otherwise it’s never going to get done." (P2) |

| Embodiment | "If you don’t contribute anything you're not really learning how to work in a team." (P4). | "If someone’s just sat there then there’s no point of them being there because they’re not a team member then at the end of the day." (P5) |

| Temporality | "Because sometimes people in your group don’t understand what you’re trying to explain, so therefore you have to go into a lot more detail." (P1) | "I think the person in charge needs to be stricter with time." (P5) |

| Spatiality | "Because in a really big class, sometimes voices get lost and don’t get heard. We have 18 groups and it gets to a point when there’s too much conversation in that room." (P5) | "As a team I think that a lot of the things you can’t understand individually comes out during the group sessions." (P1) |

| Project | "So this is good in a way that you get to hear other people’s way of thinking, and your own, and better your own knowledge." (P3) | "Like now I know everything that I learned yesterday but if I had to go for a normal exam, half of the stuff would be gone by now. Because you’re doing it as you go along and you’ve had that chance to think about it, it makes a lot more sense." (P4) |

| Discourse | "Sometimes when you argue for five minutes, with regards to answer you tend not to forget that argument. After that you don’t forget the discussion because it’s so vibrant." (P2) | "Then you argue the fact that this is right, and then someone else will say no this is it. But then you’ll argue and discuss together to come to a compromise or come to combined answer or agreement. I’ve noticed the advantage of that." (P3) |

Conclusions

The students’ lived experience suggests that TBL was well received and seems to affect their lifeworld in a positive way. This new way of teaching seemed to enhance students’ engagement and accountability and as a result positively affected their selfhood and relationships with others. Students felt motivated to come to class prepared and experienced the value of learning how to work in teams, listening to others, and contributing to a team effort. TBL takes a constructivist approach and seems to have great potential as an active learning and teaching strategy in higher education.

Authors

Joy de Vries, M.Sc., Educational scientist/faculty developer, TBL Academie, The Netherlands

Simon Tweddell, , EdD, Senior Lecturer in Pharmacy Practice, Bradford School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, University of Bradford, The United Kingdom

Rebecca McCarter, B.Sc., Educational Development Consultant, Centre for Educational Development, University of Bradford, The United Kingdom

[vc_tta_accordion active_section=”0″ no_fill=”true” el_class=”lahteet”][vc_tta_section title=”References” tab_id=”1458134585005-b3f22396-5506″]

Ashworth, P. (2003). An approach to phenomenological psychology: the contingencies of the lifeworld. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 34(2), pp 145-157.

Biggs, J. B. & Tang, K. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University, What the student does. 4th ed. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Currey, J., Eustace, P., Oldland, E., Glanville, D. & Story, I. (2015). Developing professional attributes in critical care nurses using Team-Based Learning. Nurse education in practice, 15(3), 232-238.

Chung, E.-K., Rhee, J.-A., Baik, Y.-H. & A, O.-S. (2009). The effect of team-based learning in medical ethics education. Medical Teacher. Taylor & Francis, 31(11), pp. 1013–1017. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/01421590802590553

Heidegger M. (1927). Being and Time. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hrynchak, P. & Batty, H. (2012). The educational theory basis of team-based learning. Medical Teacher, 34(10), pp. 796–801. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0142159X.2012.687120

Kaufman, D. M. (2003). Applying educational theory in practice. British Medical Journal (Clinical research ed.). Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Company, 326(7382), pp. 213–216.

Letassy, N. A., Fugate, S. E., Medina, M. S., Stroup, J. S. & Britton, M. L. (2008). Using team-based learning in an endocrine module taught across two campuses. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72(5). http://www.ajpe.org/doi/abs/10.5688/aj7205103

Levine, R. E., O’Boyle, M., Haidet, P., Lynn, D. J., Stone, M. M., Wolf, D. V. & Paniagua, F. A. (2004). Transforming a clinical clerkship with team learning. Teaching and learning in medicine. Taylor & Francis, 16(3), pp. 270–275. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/s15328015tlm1603_9

Manen van M. (2014). Phenomenology of Practice. Meaning-Giving Methods in Phenomenological Research and Writing. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press Inc.

Moon, J (2004) A Handbook of Reflective and Experiential Learning, London, Routledge Falmer.

Wright, K. B., Kandel-Cisco, B., Hodges, T. S., Metoyer, S., Boriack, A. W., Franco-Fuenmayor, S. E., Stillisano, J. R. & Waxman, H. C. (2013, December). Developing and assessing students’ collaboration in the IB programme. College Station, TX: Education Research Center at Texas A&M University. Submitted to the International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO).

[/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_accordion]