Authors: Hannelore De Greve, Jo Van de Weghe, Lien De Coninck & Jan Van de Wiele.

Abstract

In search to contribute to the closure of the performance gap between children with low SES-background and children with middle or high SES-background, our teacher training institute, Karel de Grote University College Antwerp (Belgium) developed a didactical approach, that heightens the involvement of preschoolers with low SES-background. In this approach, preschool teachers discover what children would like to experience and learn at school and adapt their activities towards these interests. The research we present addresses two questions: 1) How can we discover what children with low SES-background would like to do and learn at school? and 2) Does our didactical approach make a difference in involvement in preschoolers with low SES-background? Using design-based research, we developed a format for an exploratory activity as an answer to the first question. Switching replications helped us in determining the positive effect of the exploratory activity on the involvement of children with low SES-background.

Problem context

In Flanders (Belgium), as in other European countries, children from families with low socio-economic-status (SES) are having difficulties to perform in school at the same level as their peers with middle or high SES (Poesen-Vandeputte & Nicaise, 2010). There is no coincidence in the fact that PISA, the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, examines not only what students know in science, reading and mathematics, but also analyze the equity in education. In 2015 (and before) PISA finds that socio-economic status is linked to significant differences in performance in most countries. Belgium is known as a ‘poor student’ in this perspective, as the impact of social background and immigrant status on performance appears to be above average (OECD, 2015).

Already in preschool, there is a struggle to get children with low SES involved in activities offered by preschool teachers. In a search to contribute to the closure of this performance gap our teacher training institute, based in the super-diverse city of Antwerp (Vertovec, 2007), developed a didactical approach for preschool teachers, in order to heighten the involvement of children with low SES-background. In this approach preschool teachers try to discover the interests of children, investigate what a certain topic evokes in them, what they would like to experience and learn at school. With these insights, the teacher thinks up and adapts the educational activities towards the experiences and interests of every child in class.

As most preschool teachers have a different SES-background, they do not have a clear understanding of the life of people with a low SES-background. When they are preparing class activities, it is quite logical that they use their own frame of reference. By doing so they often miss opportunities to address the interests of children with low SES. What teachers offer them in class is poorly connected to their real life experiences and knowledge (Roose, Pulinx & Van Avermaet, 2014). We all know that learning is cumulative. Therefore, it is necessary that teachers have insight in the prior learning of pupils so they can build up new knowledge, skills and experiences (De Corte, 1996; Gagné, 1968). Next to that, we advocate the ideas of experiential education which state that children will be involved (and learn more and deeper) when they show intrinsic motivation; when they learn about things they want to learn about (Laevers, Jackers, Menu & Moons, 2014). According to these two principles and inspired by the open framework curriculum as described by Hohmann and Weikart (1995) and the emergent curriculum (Jones, Evans & Rencken, 2001) our teacher training institute elaborated a roadmap for preschool teachers with the aim of carrying out a program that is tailored to the experiences, needs and interests of the children in their class. We named it the roadmap for experiential educational practice.

Roadmap for experiential educational practice

The roadmap starts with choosing a theme together with the children. Through observation and conversation, the teacher discovers which topics are popular. Which themes are coming forward throughout the spontaneous play of children? What are they talking about to each other? What topics are coming up in the morning circle talk? Etc. Most of the time these themes refer to the real-life-experiences of the children, for example the birth of a baby brother, a huge exhibition of Lego® in the city, snow during winter, a mum who is afraid of spiders, etc. Based on these observations the teacher selects one or more themes, which he/she presents to the children for voting. The decision about what theme they will learn about in the following weeks is made together.

In the second step, the teacher prepares and introduces an exploratory activity of the theme together with the children, where they try to find the answer to the following questions:

- What is the meaning of the theme for the children in our class?

- What does this theme evokes in them (feelings, spontaneous reactions, …)

- What do they already know and what are their experiences with the theme

- What do the children want to learn about the theme? What questions do they have?

- What do the children want to do, experience, try out, … in the context of the theme?

Based on the input of children in the second step the teacher prepares a temporary plan for the coming two (or more) weeks. This plan consists of a fair amount of educational activities customized towards the learning interests and needs of the children in the class. The particularity of this plan is that it is temporary and that it does not fill the whole schedule. There are open spaces left that can only be filled in after a few days working on the theme. Throughout careful observation, conversation with the children and reflection the teacher adjusts and completes the plan according to the involvement, interests and needs of the children. This means that the teacher does not know how a theme will end, because he/she is trying to follow the children’s initiatives. For example: while working, playing and learning around the theme ‘police’ the children show fascination for the fact that some policemen ride horses. When the teacher is sensitive towards this signal he/she can start preparing activities where the children can learn more about riding horses and horses in general. In this way, the theme ‘police’ ends up with a complete different focus than the teacher could have imagined before.

Research questions

Since 2010, we ask student-teachers to use our roadmap for experiential practice during their internships. From their experience, we learned a lot about the applicability and the usefulness of the roadmap and we had to admit that there was room for improvement, especially in addressing children with low SES. Next to that, we felt the need to make our didactical approach more evidence-based (Davies, 1999). For years we passed along our enthusiastic beliefs in the experiential way of working with young children, but we never investigated its actual effectiveness. A new research proposal was born.

During our practice-based research, we addressed two research questions:

- How can we improve step 2 of our roadmap (exploratory activity), in order to better understand what children with low SES-background would like to experience and learn at school?

- Does step 2 of our roadmap (exploratory activity) influence the involvement of preschoolers with low SES-background?

For reasons of reliable and valid research we narrowed our focus in both research questions on one step of the plan, namely exploring a theme (for example ‘my house’, ‘spiders’, …) together with children. Because of the aim for inclusive didactics, we also studied the effect of this step on the involvement of preschoolers with middle or high SES.

Methodology

As for the first research question, we used design-based research (DBR) to optimize the format of the exploratory activity with 4- to 5-year-olds. This approach bridges the gap between research and educational practice and is used for the development and refinement of didactical tools (Schoenfeld, 2009). In DBR, research is done in cooperation with practitioners in authentic contexts (Reeves, 2006). As for that, eight experienced teachers (teaching in our super-diverse city) tried out the exploration of a theme together with their children and helped us consider what works, when we try to find out what children with low SES want to learn about. We gathered data in three iterative cycles and used multiple data gathering instruments: video recordings, reflection forms, semi-structured interviews and in-depth group discussions. All data were transcribed and then analyzed by an open and double coding process in search for patterns, relations and factors for success. The conclusion of this process was a clearly described format of the exploratory activity with 4- to 5-year-old children, which has been proven effective. This means that a preschool teacher can get a reasonable understanding of what the theme evolves in children with low SES, what it means for them and what they would like to experience and learn about it.

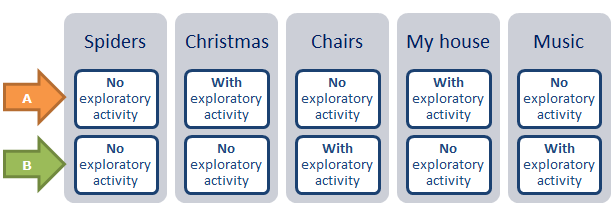

As for the second research question, we used the model of switching replication (Shadish, Cook & Campbell, 2002) in eleven classes to measure whether the new format of the exploratory activity resulted in higher involvement of the children. In switching replications, respondents are alternately assigned to the control and the experimental group. The major advantage of this method is that there is no need to control for nuisance variables, such as teacher characteristics. So when a first group of teachers (A) was asked to explore a fixed theme together with their children and adjust their activities towards the input of the children, the other group (B) was asked to simply prepare activities within the fixed theme (without the exploratory activity as starting point). On a later moment, with a new fixed theme, group A represented the control group and did not execute the exploratory activity and the former control group (B) did. The design started with a baseline measurement within the theme ‘spiders’. ‘Christmas’, ‘chairs’, ‘my house’ and ‘music’ were the following themes (cf. figure 1). Although imposed themes are not in line with the first step of the roadmap, we needed to assure that as much variables as possible were constant and not interfering in the measured involvement. After all the focus of our research question was step 2 and not the roadmap as a whole.

All classes were working on the same theme in fixed weeks. During these weeks, we measured the involvement in eleven classes, applying the Leuven Involvement Scale for Young Children (Laevers, Depondt, Nijsmans & Stroobants, 2008). High involvement is a state in which the child is completely absorbed by an activity; operating to your full capabilities; it is challenging and therefore you show concentration, creativity, precision, energy and persistence (Laevers, Jackers, Menu & Moons (2014). This means that observing high involvement is to see somebody developing and learning. The Leuven Involvement Scale for Young Children defines five levels of involvement, starting from complete absence of involvement (1), to mainly continuous activity without signals for involvement (3), ending with the highest possible involvement (5). In the scanning procedure, you set a score for involve after observing a child for a few minutes (Laevers & Laurijssen, 2001; Van Heddegem, Gadeyne, Vandenberghe, Laevers & Van Damme, 2004). For reasons of reliability we observed each child twice during a theme (2×4 scannings) during morning or afternoon (Laevers, Depondt, Nijsmans & Stroobants, 2008). The average of these eight scores was used as an estimation of involvement of that child according to the theme-activities.

We analyzed the data from 119 children using a mixed model design, with ‘condition’ and ‘socio-economic status’ as predictors and ‘involvement’ as dependent variable. This multi-level model takes into account that children (level 1) are nested in classes (level 2), which implies that those observations are not independent.

At the end of every theme, the preschool teachers were interviewed to give more insight in factors that potentially influenced the observed involvement. In addition, the interviews provided some kind of follow-up for the participants in order to optimize the operationalization of the experimental condition.

Results

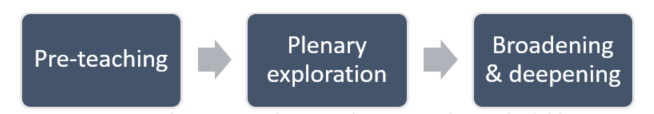

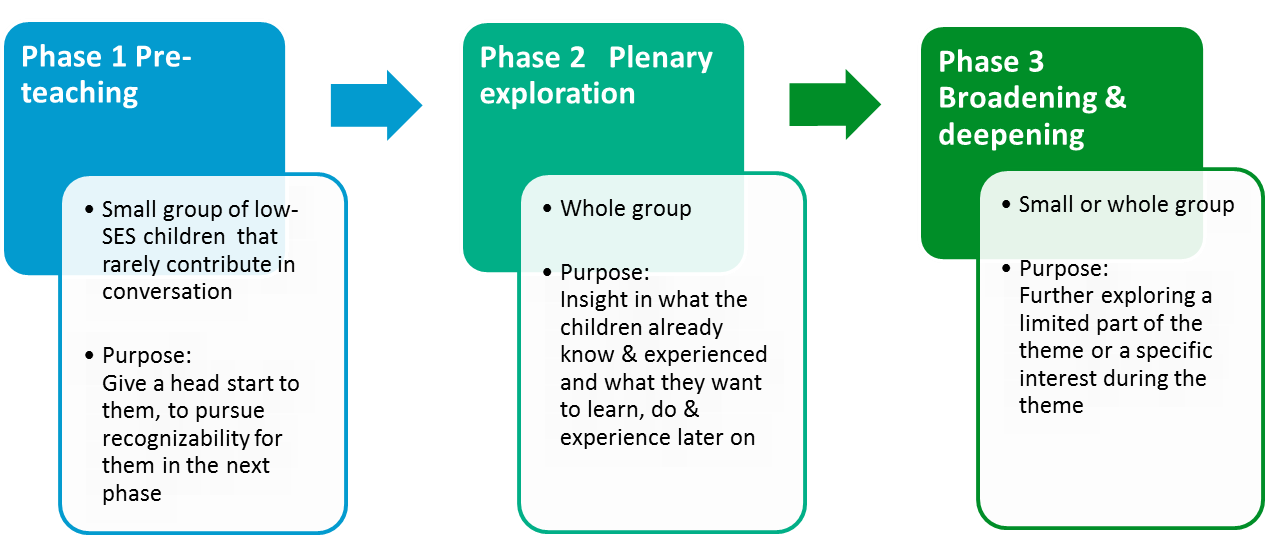

The core finding for the first research question was the idea to have different phases in exploring the theme with children (cf. figure 2).

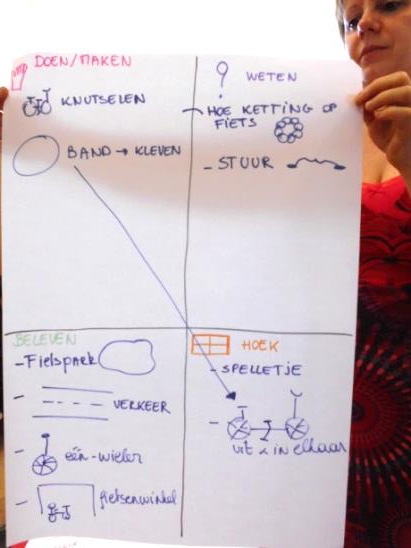

Our format, developed through design-based research, starts with a phase of pre-teaching for low-SES children whose contribution to exploring activities normally is low or even lacking. For teachers it is difficult to find out what the themes mean for those children and what they would like to experience and learn. By giving them a head start in a small group, they are more activated and come up with some input and ideas. When the teacher explicitly refers to their input during the plenary exploration (phase 2) with the whole group, the well-being and involvement of these children increases. Because of that they also dare to speak more than they are used to. In interaction with the teacher and the other children they deepen their own ideas and comment on ideas of others. The plenary exploration that should be recognizable for the pre-teaching group, results in a brainstorm of ideas that the teacher uses to prepare a week plan (cf. figure 3).

During the theme, it turned out to be very interesting to further explore the chosen theme with the children. In a third phase a limited part of the theme (a specific interest) is broadened or deepened together with the children, resulting in more ideas for activities for the coming days. A successful method for phase 3 is setting up a new corner together with the children.

In our research for example, a teacher followed the input of a child that had never showered before, because she only has a bathtub at home. Another child came up with the idea of building a shower in the classroom. Together with a small group of children, they thought about what they would need to build a shower, what accessories they would need, what steps they would follow, etc. For some children it is easier to think along when the brainstorm is about a more delineated subject and some children need more time to come up with ideas or need to be immersed in a theme before they can start making plans.

In figure 4, we present the final format as the answer to our first research question: How can we improve step 2 of our roadmap (exploratory activity), in order to better understand what children with low SES-background would like to experience and learn at school?

Next to the phasing, we also found five didactical guidelines in exploring a theme together with children:

- Before you expect children to bring in ideas, give them a strong impression about the theme. Bring some materials with you, show them a video clip, take them out for an excursion, etc.

- Combine conversation with playing and doing. You can get insights in what the children want and need by listening to them, but also by observing them carefully. Instead of talking about what music they like, put them on a stage with a microphone and look what they bring to you. Instead of asking what happens in a hospital according to them, give them a Playmobil® hospital and observe their spontaneous play.

- Support children in formulating their ideas. For example during a theme exploration about volcanoes, a girl said “Little rocks are flying”. As a reaction to the teachers question: “What do the rocks look like?”, she says “orange, with fire”. The teacher verifies “Do you mean that lava stones are coming out of the volcano when it is erupting?”.

- Visualize the ideas of the children and mark the ideas when you have fulfilled them. For example, you can place all ideas on a green blackboard and move them to a red blackboard when accomplished. Use this in a conversation with your children: maybe they have more ideas to fill the green blackboard again; maybe they are not interested anymore in some items on the green blackboard. Doing a re- and preview with your children is recommended: thinking about what you have done and what you still want to do, empowers them in sharing ideas, taking initiative, etc.

- Emphasize that these ideas are their ideas. We saw how children were really proud and involved when they knew that they came up with the idea for this particular activity. They feel acknowledged. In doing so children experience that their ideas are really taken into account, which leads to more ideas the next time you explore a theme with them. This observation can be linked to the idea of epistemic agency in Knowledge Building theory (Scardamalia, 2000; Scardamalia & Bereiter, 2006). Teachers turn agency over to the children so that children can take responsibility in their own learning process.

Although it was not the focus of our research, teachers tentatively stated that children with low SES more often came up with things they wanted to do, try out, explore and experience, while children with high SES were more likely to come up with specific questions they want answers for. In trying to understand reality, it seems that children with low SES are more relying on their senses and children with high SES are more likely to approach reality in a cognitive way. Of course, these statements are premature findings that need to be investigated more in depth in the future.

We set up a quasi-experimental design to find an answer to the second research question: Does step 2 of our roadmap (exploratory activity) influence the involvement of preschoolers with low SES-background? The idea behind this research question is that we believe that learning activities in our Flemish preschools are not connected enough with the perspective of children with low SES. With our exploratory activity, we help teachers to get connected with this perspective and we ask them to address specific learning interests and needs of these children in their preparation for activities. The question is whether this results in a higher involvement of the children with low SES and hence in more and deeper learning effects. If we can prove this, we have something that can help us to bridge (or maybe even to prevent) the performance gap between children with low SES and the others.

In analyzing the data (3081 individual involvement scores; 523 average involvement scores), we found promising results. Exploring a theme together with children, following the instructions of the provided format, leads to significant higher involvement, both for children with low as for children with middle or high SES, F (1, 441.789) =8.99, p = 0.003. Interesting to know is that we also detected a general difference in involvement between children with low SES-background and the other children (F (1, 245.357) = 4.559, p = 0.034). This confirms our initial research problem stating that there is a challenge for low SES-children in Flemish education. To sum up, we found significant main effects for socio-economic status and condition (with or without exploratory activity), but did not find a significant interaction effect between these predictors. As we aspire an inclusive approach, this was the best result we could hope for. Both children with low SES and children with middle or high SES are benefiting from a teacher that prepares activities based upon an exploration of the theme together with them.

To end with, we would like to share a last outcome, though it was not the focus of our research. Comparing 60 boys to 59 girls, we could not find a significant difference in involvement according to gender. As we often experience that our primary education is more directed towards girls, we think it is hopeful that this appears not to be the case for early childhood education.

Conclusion & discussion

Society is confronted with an increase of socio-economic differences and education faces many challenges in this perspective. Because education towards children until they are six years old is crucial for the social, emotional and cognitive development and could be the lever to reverse the negative impact on children living in vulnerable contexts (Roose, Pulinx & Van Avermaet, 2014), we should extend research on this topic and make new findings accessible for all.

In this research study, we examined our didactical approach towards education for young children. Building upon the ideas of experiential education, open framework and emergent curriculum we developed a roadmap for preschool teachers that they can use to let children participate in deciding what they want to learn and what they want to do and experience at school. Two questions came up: 1) How can we know what children with low SES-background want to learn and experience? and 2) If we offer activities based upon the ideas of all the children in our classes (low, middle and high SES), will the children be more involved?

In answering the first question, we can give preschool teachers guidance in how to gain more insight in what a theme means for children with low SES-background and what they want to learn about. As for this ‘format’ (illustrated more thoroughly above), we need to emphasize that this only works with 4- to-5-year-old children. In our follow-up research we are developing a format for the youngest children in Flemish education, who are 2.5 to 3 years old. Preliminary results suggest again a multi-phased design, where in depth observation of play plays a very important role.

Finding a significant effect of the exploration of the theme together with children on their involvement in class is very important. This means we can use this didactical approach to enhance learning in preschool, both for children with low SES and for children with middle or high SES. Of course, we also wonder whether this approach could work in primary, secondary and even higher education. We believe that education should make more use of the intrinsic motivation to learn about reality, the urge to explore – something every person initially holds. It is a way of empowering people in their learning process and even in the way they want to lead their lives.

At the end of this article, we would like to point out that doing research together with practitioners is very enriching for both parties. We could experience the fact that design-based-research bridges the gap between educational research and practice. Together, as colleagues, we examined the obtained data, we discussed and suggested preliminary answers on our research question. Based on those answers they went back to their classrooms to try out a new format. This practice was again the starting point for a new cycle in the design-based-research set-up. The teachers, involved in our research, were praising the beneficial effects of the participation in this project. Reasons for this were the acknowledgement of their expertise, the chances to share ideas and experiences with peers and researchers and the opportunity to reflect upon their every-day-practice in a more profound way. Participating in this research meant a profound and sustainable way of professionalization for these preschool teachers.

Authors

Hannelore De Greve, M.Sc. (Ed.), Teacher educator, Karel de Grote University College, Belgium

Jo Van de Weghe, M.Sc. (Ed.), Teacher educator, Karel de Grote University College, Belgium

Lien De Coninck, M.Sc. (Ed.), Teacher educator, Karel de Grote University College, Belgium

Jan Van de Wiele, M.Sc. (Ed.), Teacher educator, Karel de Grote University College, Belgium

[vc_tta_accordion active_section=”0″ no_fill=”true” el_class=”lahteet”][vc_tta_section title=”References” tab_id=”1458134585005-b3f22396-5506″]

Davies, P. (1999). What is evidence-based education? British Journal of Educational Studies, 47, 108‒122.

De Corte, E. (1996). Actief leren binnen krachtige onderwijsleeromgevingen. Impuls voor onderwijsbegeleiding, 4, pp. 145‒156.

Gagné, R. M. (1968). Contributions of learning to human development. Psychological Review, 75(3), 177‒191.

Hohmann, M. & Weikart, D.P. (1995). Educating young children: active learning practices for preschool and child care programs. Michigan: High/Scope press.

Jones, E., Evans, K. & Rencken, K.S. (2001). The Lively Kindergarten. Emergent curriculum in action. Washington: the National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Laevers, F., Depondt, L., Nijsmans, I. & Stroobants, I. (2008). De Leuvense betrokkenheidsschaal voor kleuters. Averbode: Cego Publishers.

Laevers, F., Jackers, I., Menu, E. & Moons, J. (2014). Ervaringsgericht werken met kleuters in het basisonderwijs. Averbode: CEGO publishers.

Laevers, F. & Laurijssen, J. (2001). Welbevinden, betrokkenheid en tevredenheid van kleuters en leerlingen in het basisonderwijs. Een draaiboek voor systematische observatie en –bevraging: eindrapport (OBPWO-project 98.07). Leuven: K.U.Leuven, onderzoekscentrum voor kleuter- en lager onderwijs.

OECD (2015). PISA 2015 results (Volume I). Excellence and equity in education. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264266490-en

Poesen-Vandeputte, M., & Nicaise, I. (2010). De relatie tussen de doelgroepafbakening van kansarme kleuters en hun startpositie op school (SSL-rapport nr. SSL/OD1/2010.26). Leuven: Steunpunt Studie- en Schoolloopbanen.

Reeves, T. (2006). Design-based research from a technology perspective. In J. V. D. Akker, K. Gravemeijer, S. McKenney & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational Design-based Research (pp. 52‒66). New York: Routledge.

Roose, I., Pulinx, R. & Van Avermaet, P. (2014). Kleine kinderen, grote kansen. Hoe kleuterleraars leren omgaan met armoede en ongelijkheid. Kortrijk: drukkerij Jo Vandenbulcke.

Scardamalia, M. (2000). Can schools enter a Knowledge Society? In M. Selinger and J. Wynn (Eds.), Educational technology and the impact on teaching and learning (pp. 6‒10). Abingdon, RM.

Scardamalia, M. & Bereiter, C. (2006). Knowledge building: Theory, pedagogy, and technology. In K. Sawyer (Ed.), Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences (pp. 97‒118). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (2009). Bridging the cultures of educational research and design. Educational Designer, 1(2). Retrieved from http://www.educationaldesigner.org/ed/volume1/issue2/article5

Shadish, W.R., Cook, T.D. & Campbell, D.T. (2002). Experimental and quasi experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Wadsworth: Cengage learning.

Van Heddegem, I., Gadeyne, E., Vandenberghe, N., Laevers, F. & Van Damme, J. (2004). Longitudinaal onderzoek in het basisonderwijs. Observatieinstrument schooljaar 2002‒2003. Leuven: Steunpunt LOA, unit onderwijsloopbanen.

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024‒1054.

[/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_accordion]